At 28, degree in hand and with the desire to build something of his own, Marco believed that becoming a taxi driver in Athens would be a simple road to financial independence. He was wrong. The taxi license alone costs roughly €80,000 to €120,000—an amount that, in practice, requires a crushing loan, with no realistic prospect of repayment on a taxi driver’s income. Add the cost of the vehicle (€15,000–25,000 for a reliable one), insurance, fuel, and maintenance, and the barrier to entry becomes insurmountable.

But Marco, like thousands of other young Greeks, discovered there is another “solution”—one that is somehow even worse than the impossible dream of ownership: he can rent a license.

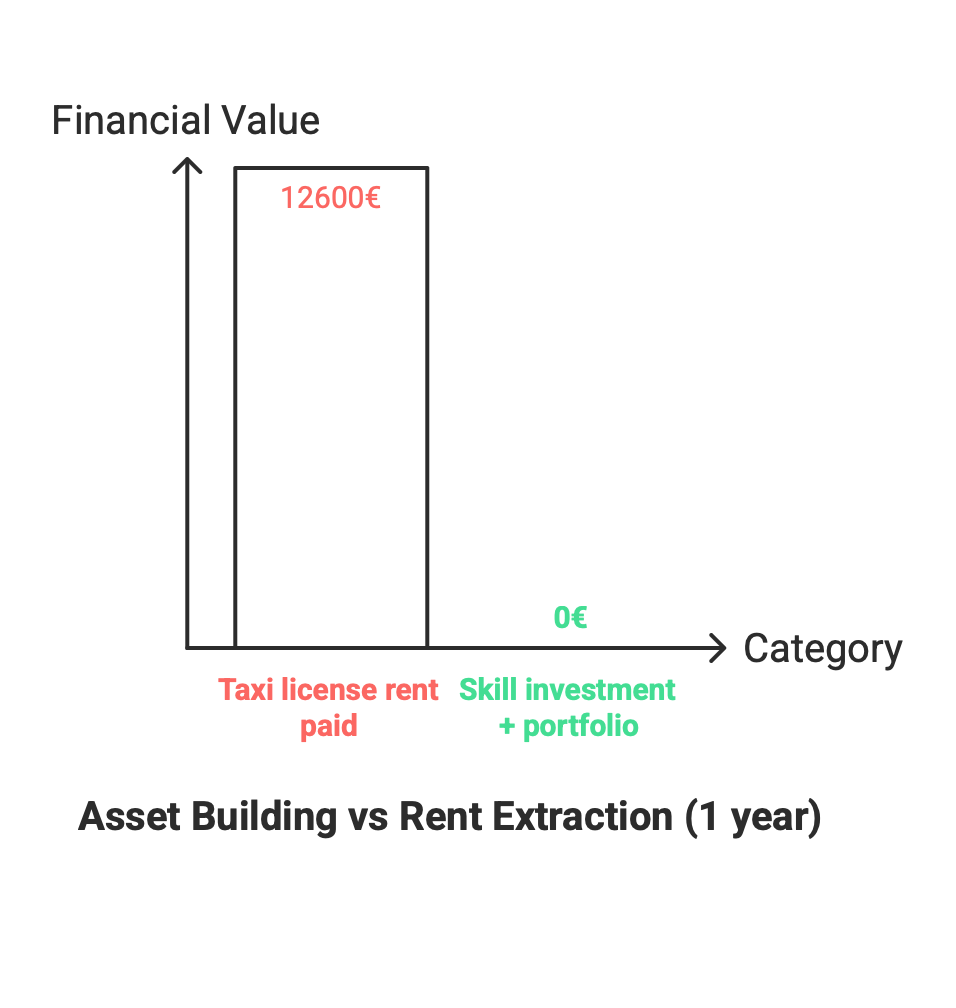

For €35 per day, seven days a week, Marco can rent someone else’s license (and often the vehicle). Do the math: €1,050 per month or €12,600 per year, paid directly to a license owner who does nothing other than collect “rent” on an asset they likely inherited or bought decades ago, when prices were a fraction of today’s. This rent is taken “off the top,” before Marco pays for fuel (€80–100 per day on a full shift), before maintenance and repairs, before his own living expenses—before everything.

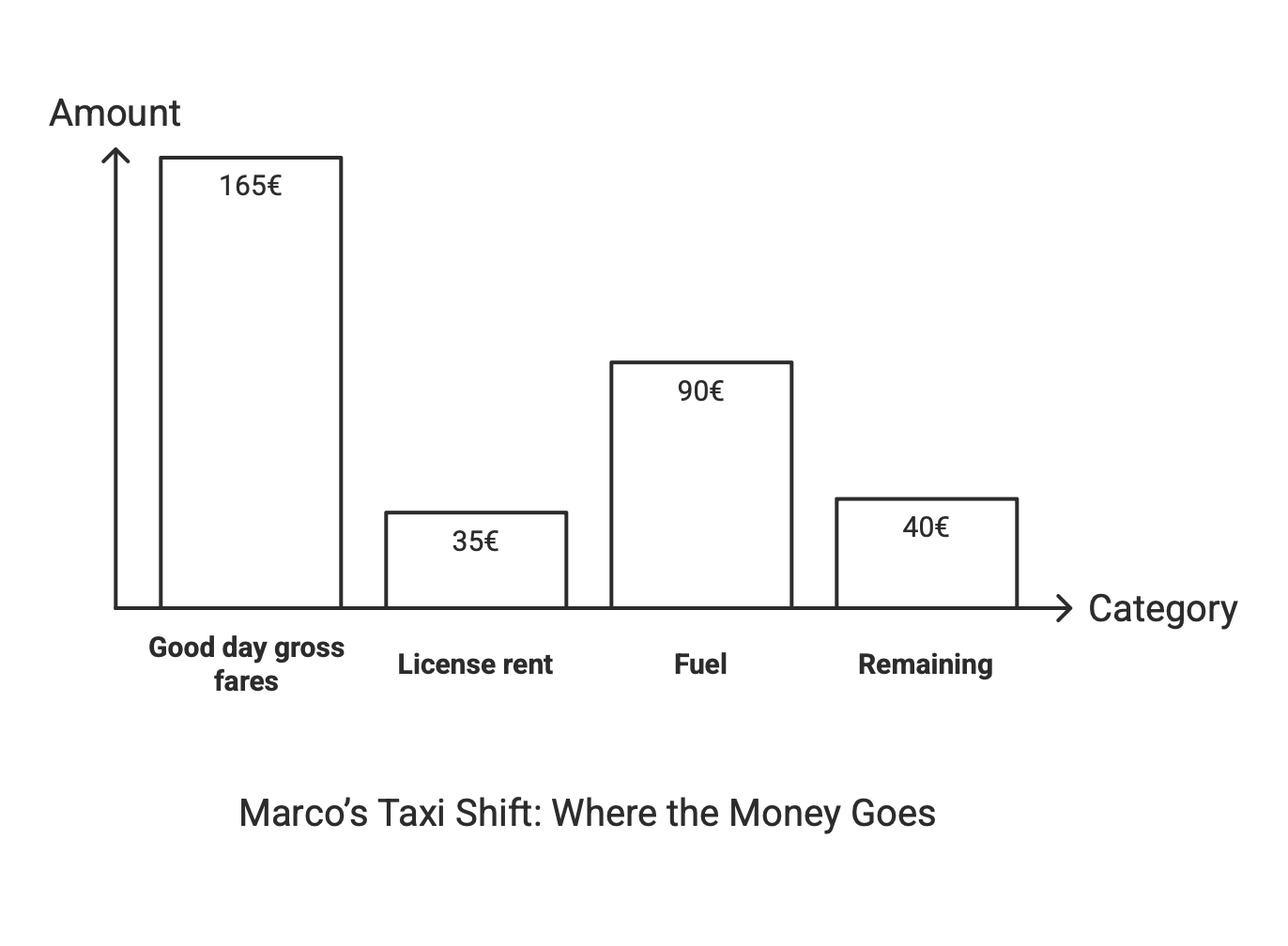

On a good day, he might gross €150–180 in fares. If he subtracts the €35 rental fee and about €90 for fuel, he is left with €25–55—and that’s before accounting for inevitable breakdowns, insurance contributions, and the percentage often withheld from card transactions. On a bad day, he might not even cover the basics or may even lose money, but he still owes the €35 anyway—whether he had customers or sat empty in traffic for hours.

The rent is not negotiable. And it never stops. Marco gets exactly two days off per month—not per week, per month. That means 28 days of mandatory work just to pay someone else, for the “privilege” of exhausting himself 10–12 hours a day in Athenian traffic. And those two days aren’t even guaranteed to be weekends or consecutive. They are set by the license owner, often strategically placed on the slowest commercial days of the month.

The outcome for Marco’s life is almost predetermined. He wakes up at 5 a.m. for early airport runs and the first commuters. He works until 6 or 7 p.m., battling traffic, managing difficult passengers, breathing exhaust fumes, developing back pain from prolonged sitting. He has no time for friends, no energy for relationships, and no ability to build a normal social life. While old classmates who left for Germany or the Netherlands go out for a drink after work or build a routine, Marco is in his 14th hour behind the wheel calculating whether he made enough to cover the €35 and the fuel.

The cruelty runs even deeper when the union declares a strike—something that happens often, as license owners (not renters like Marco) protest ride-sharing apps or demand fare increases. When there’s a strike, taxis don’t operate. There are no rides, no income. But Marco still owes the €35 for that day. The license owner never “strikes”: their income is guaranteed whether Marco works or not, whether there is a protest or not, whether there is a pandemic or an economic crisis.

So Marco faces an impossible dilemma during strikes: participate, lose the day’s earnings and still pay the rent, sinking deeper into the void; or break the strike, risk confrontation with other drivers and “enforcers,” and try to earn from a few desperate customers what he needs just to avoid drowning. Either way, he loses. The license owner never loses.

After six months, Marco has saved nothing. He is permanently exhausted, socially isolated, and not even closer to buying a license. In fact, he is farther away. The €12,600 he paid in rent that year could have been a down payment on something, an investment in skills, capital to build real ownership. Instead, it became a subsidy for someone else’s retirement—someone who may have bought the license 30 years ago for €15,000 and now collects passive income from the desperation of the young.

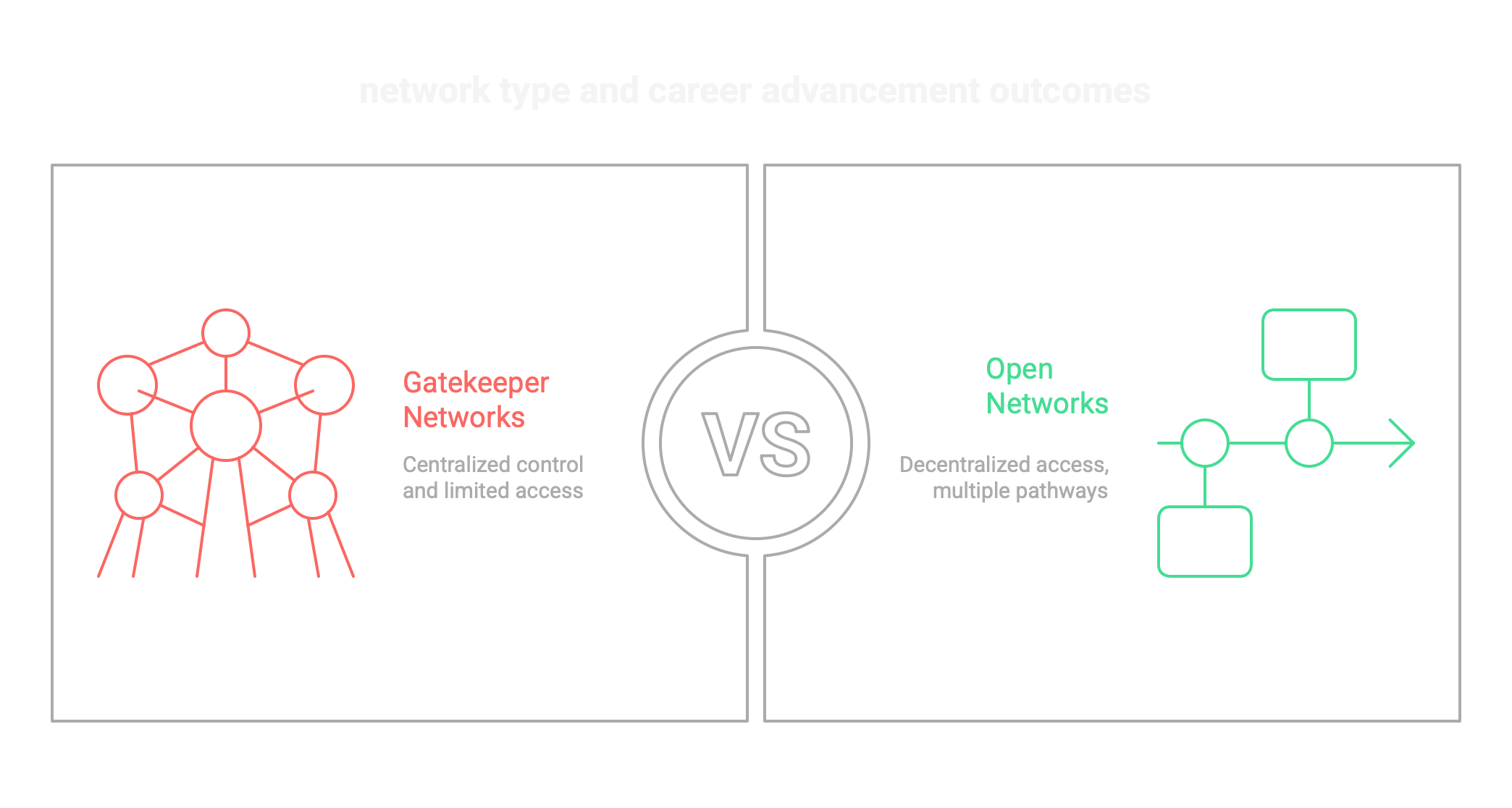

Unions that once defended workers’ rights have, in many cases, fossilized into mechanisms for guarding privilege. They don’t represent Marco. They represent the license owners who exploit him. When the union fights ride-sharing apps, it isn’t necessarily protecting Marco’s ability to earn; it is protecting the asset value of the owners. Marco is not a worker being protected—he is a revenue stream being preserved.

And Marco is not an exception. He is the story of an entire generation in Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal, and in similar economies worldwide, where young people face a labor market that has, essentially, fortified itself against them.

The Mathematics of Despair

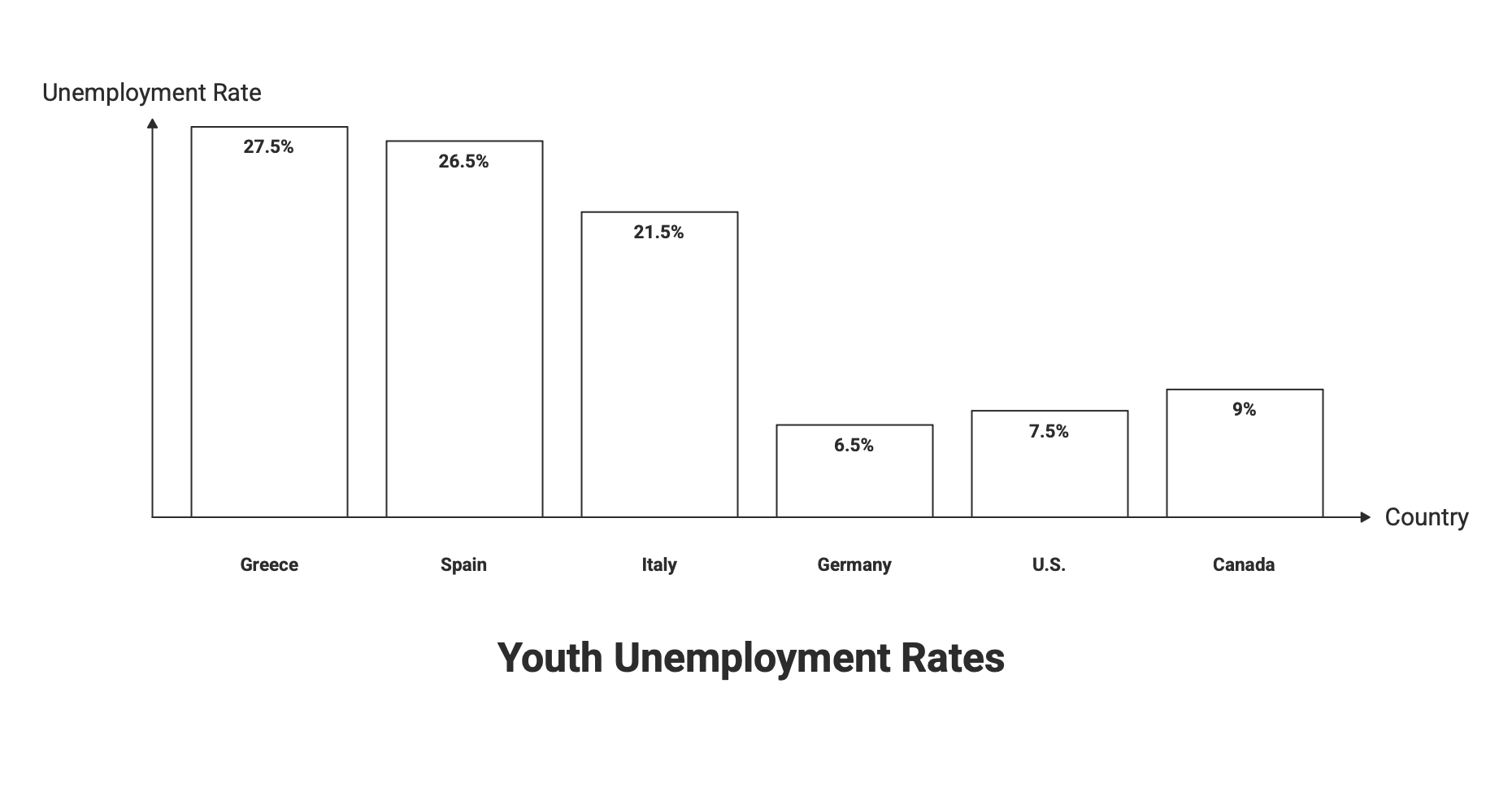

The numbers are relentless. Youth unemployment in Southern Europe remains consistently among the highest in the developed world. Based on recent data, youth unemployment in Greece hovers around 25–30%, in Spain 25–28%, and in Italy roughly 20–23%. Compare that to Germany (6–7%), the U.S. (7–8%), or Canada (8–10%), and the difference becomes deafening.

But unemployment tells only part of the story. The more insidious part is underemployment and the dominance of precarious forms of work. In Italy, nearly 30% of young workers are on temporary contracts without job security, compared to about 13% in Germany. In Spain, the share for workers under 30 reaches 35–40%. These contracts aren’t a step toward stability—they’re a treadmill that keeps you running in place.

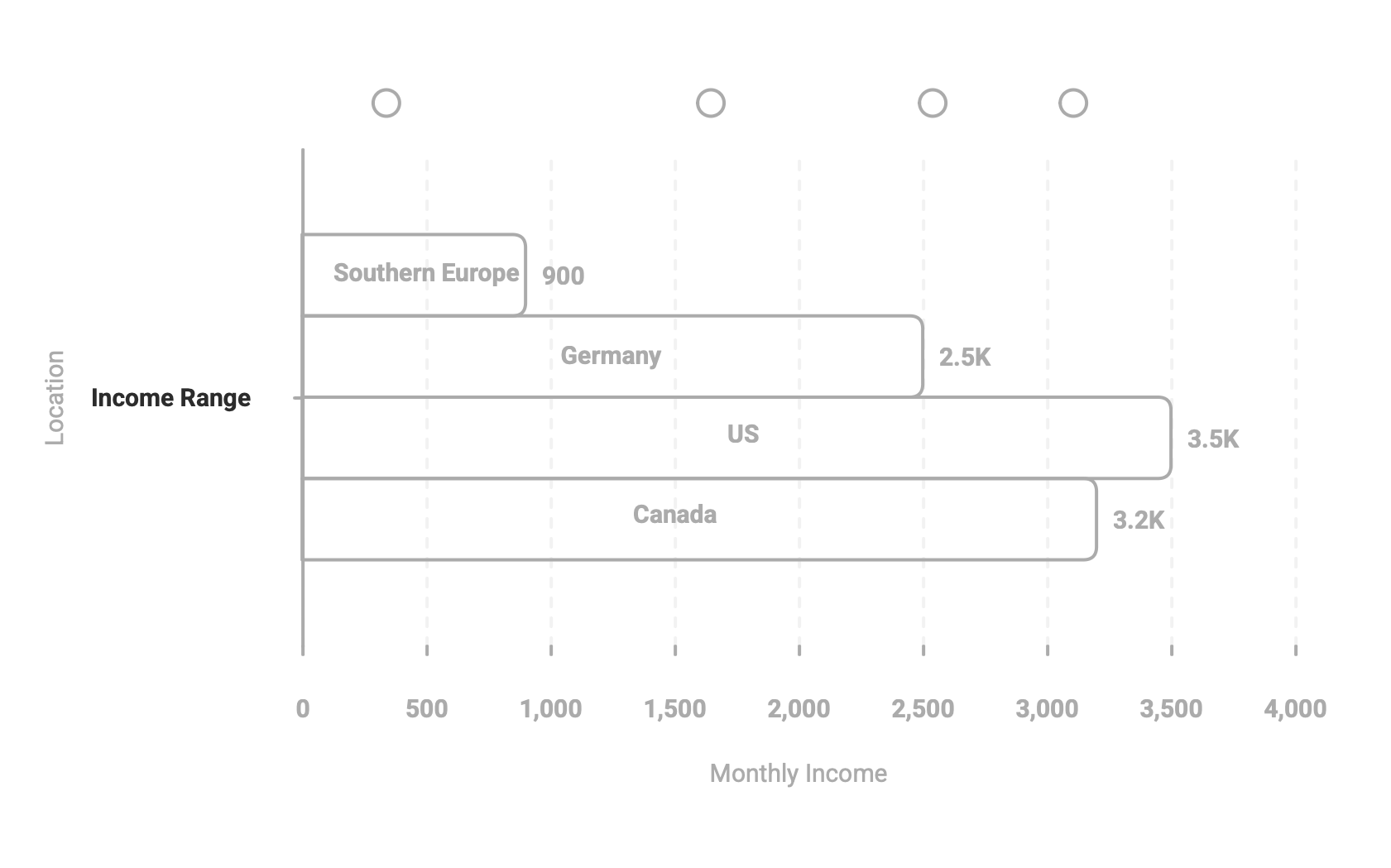

Then there’s the wage gap. A young 25–30-year-old in Southern Europe with a degree typically earns €900–1,400 per month in entry-level roles—often less in practice.

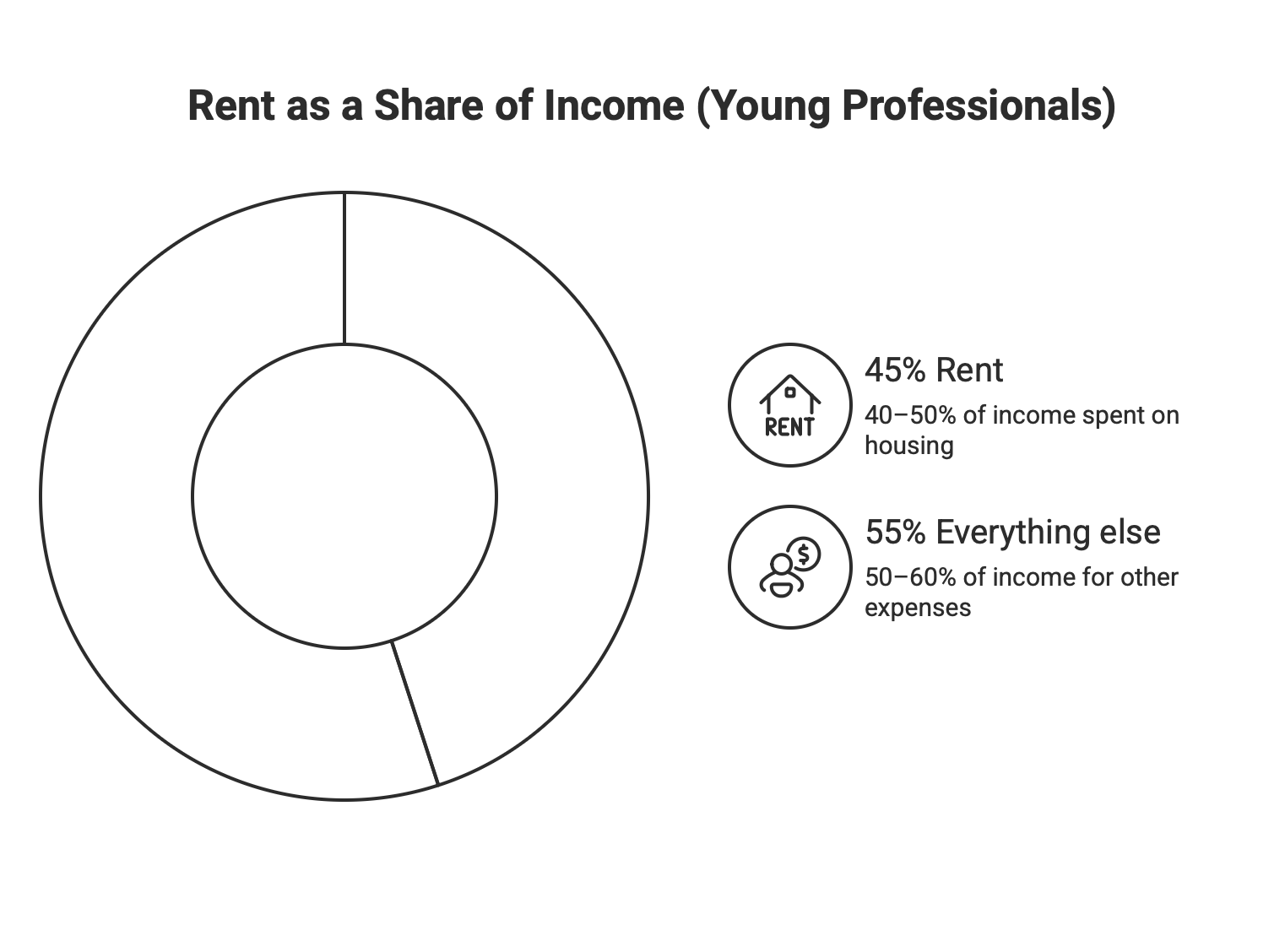

In Germany, a comparable worker may start at €2,500–3,200; in the U.S. at $3,500–4,500; and in Canada at CAD 3,200–4,000. And when you add the cost of living, the picture darkens further. A young professional in Athens or Madrid may spend 40–50% of their income on rent alone, leaving little for savings, emergencies, or the ability to start a family.

Closed Professions

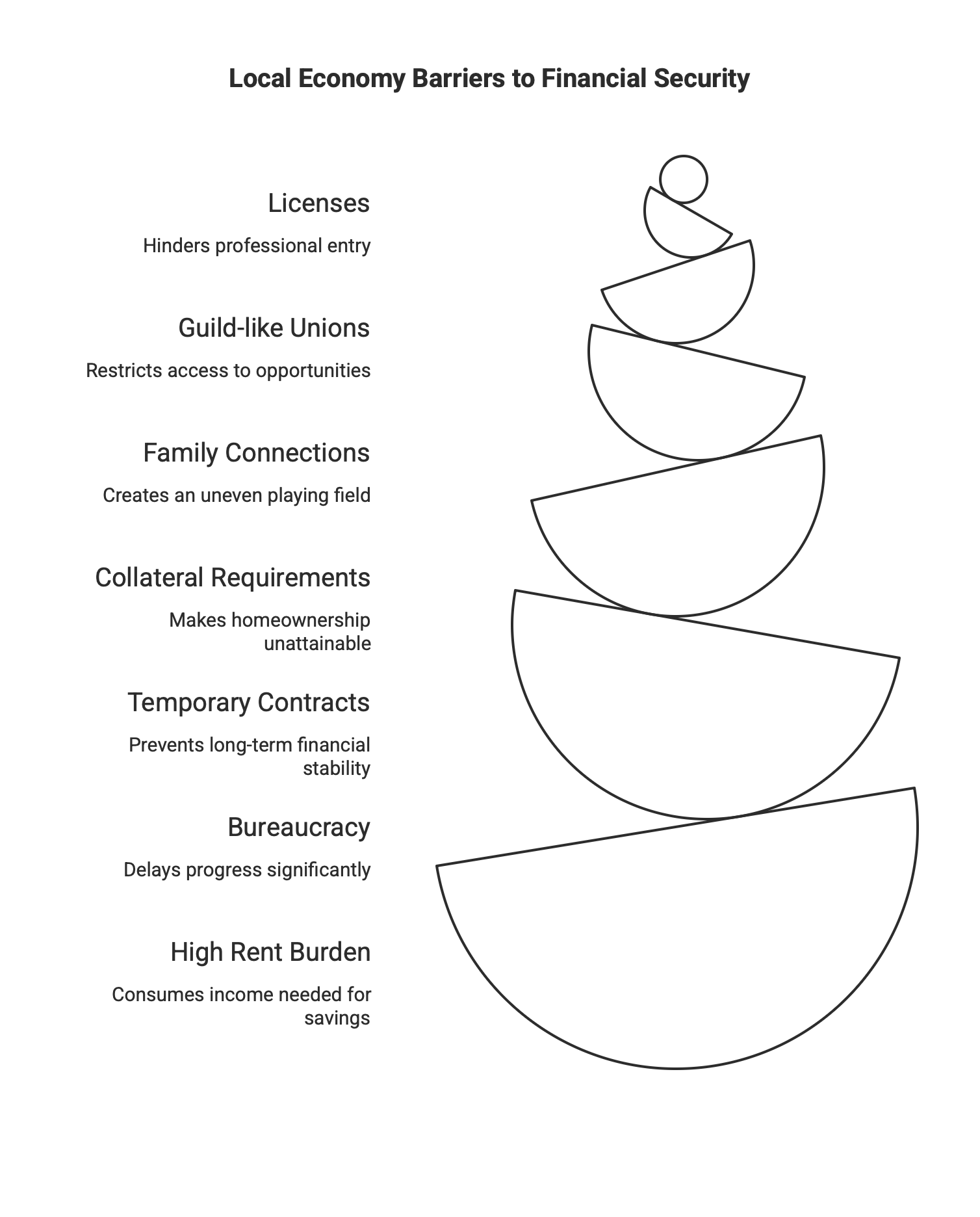

Beyond taxis, Southern Europe’s labor market is full of professions that have become nearly inaccessible without significant family wealth or connections.

In pharmacies, for example, in Greece and Italy, opening one requires purchasing a license that can cost €200,000–500,000 depending on the area. Licenses are strictly limited, and existing owners fiercely protect local monopolies. A new pharmacy graduate is forced to choose: remain underpaid for years as an employee or emigrate.

In notarial services, especially in Italy and Spain, entry is a multi-year process with highly competitive exams where success rates may be 2–5%. Even after passing, many wait years for a position to open, usually through retirement or the death of an existing notary. These roles are extremely lucrative (€150,000–300,000 annually), but the barriers to entry make them almost “hereditary.”

In law, although it is theoretically an open profession, in practice many young lawyers spend 3–5 years in unpaid or minimally paid training (€300–600/month) in expensive cities, forced to survive without meaningful income.

Similar barriers exist in medicine (long training and the expensive start-up of a private practice), architecture (years of low pay and high costs for insurance/infrastructure), imports–exports and customs (licenses, guarantees, capital, and networks), hospitality/food service as ownership (€50,000–200,000 in start-up capital in tourism-dependent economies), even in “technical” trades like plumbing/electrical work, where certification pathways, exams, and market structures often function as deterrents.

Systemic Suffocation

The most dangerous element is that this crisis is systemic. The barriers are not an accident, they are a feature of economies that prioritized protecting existing “insiders” rather than creating opportunities for young “outsiders.” Unions that once defended labor now operate like medieval guilds, restricting supply to keep profits high for those already inside, excluding everyone else. Professional associations label excessive restrictions as “quality control,” while essentially shielding incumbents from competition. Banks won’t lend to young people without collateral, which young people can’t acquire because they can’t access good jobs.

And bureaucracy worsens the problem. Starting a business in Greece can require 6–12 months and thousands of euros in legal/administrative costs. In Spain, the tax burden on new businesses can absorb 30–40% of revenue even when they’re barely surviving. In countries like Estonia, you can establish a company online in less than a day. In the U.S., you can set up an equivalent LLC in under a week with a few hundred dollars. The comparison is not flattering.

The result is not only individual hardship. It is economic stagnation. When young people cannot enter the market on reasonable terms, they don’t accumulate capital and don’t take entrepreneurial risk. The economy stays stuck. Innovation dies. Productivity collapses. Dynamism gives way to gerontocratic rigidity.

Demographic Collapse

The consequences go beyond economics. Southern Europe is experiencing a demographic collapse that threatens its viability. Italy’s birth rate has fallen to 1.24 children per woman, Spain’s to 1.19, Greece’s to 1.32, and Portugal’s to 1.35, when 2.1 is needed for a stable population. The link to young people’s economic insecurity is direct: when you are 30, living with your parents because you can’t pay rent, working on a temporary contract that can end at any time, and earning €1,100 per month, having a child isn’t just difficult—it feels irresponsible.

The average age of first motherhood in Spain is 32.6, in Italy 31.4, in Greece 30.8. It’s not that women “choose careers over family”; it’s that many simply can’t afford a family until their 30s+, if ever. And then windows narrow, difficulties rise, and family sizes shrink.

This creates a vicious cycle: fewer young workers means fewer contributions to pensions and social security, while the elderly population grows. The tax burden shifts onto fewer workers, reducing their ability to save or invest. The state borrows more as age-related spending increases. Investment in education and infrastructure declines. The economy orients increasingly toward retirees’ needs instead of creating opportunities for the young.

When there is no future, the most capable leave. Since 2008, Italy has lost over 800,000 young people through emigration, disproportionately educated and specialized. Greece has lost roughly 500,000 since the economic crisis, about 5% of the total population. Similar outflows exist elsewhere. These people aren’t leaving for “experiences.” They are economic refugees from countries that offer them no future.

They go to Germany, where unemployment is low and wages are high. They go to Canada and Australia, which actively recruit skilled immigrants. They go to Gulf countries, trading cultural hardship for opportunity. And often they don’t return.

So the very human capital these countries need to renew themselves is lost. The most entrepreneurial, the most educated, the most mobile, the ones who could challenge the old and build new sectors, are the ones who leave. What remains is an economy increasingly split between protected insiders aging in guaranteed positions and outsiders fighting for scraps.

Even if Southern European countries reformed everything tomorrow, licenses, bureaucracy, labor markets, housing, the generation that would have had children in their 20s is already in their 30s. The children not born in 2015 won’t enter the labor market in 2035. The workers who won’t exist in 2035 won’t pay pensions in 2060. Demographic math is unforgiving.

At its core, this is a crisis of the social contract. The postwar promise was simple: work, study, follow the rules, and you will have a chance to build a decent life. That contract has broken in Southern Europe. Young people did “what they were supposed to”: they stayed in school, earned degrees, want to work. And as a reward, they are offered temporary contracts, poverty wages, and the prospect of living with their parents into middle age.

The political consequences are already visible: radicalization, shifts toward populist movements, collapse of trust in institutions, low youth participation in elections. When a generation believes the game is rigged, social cohesion dissolves. And then it’s not only the economy that is at risk, the democratic rules are at risk too.

The Global Dimension of Exclusion

But this crisis isn’t only European. It is global.

In South Africa, youth unemployment has reached levels of social devastation: 46.1% for ages 15–34 in the first quarter of 2025 and 60.8% for ages 15–24 in mid-2024. In provinces like North West and Eastern Cape, rates approach or exceed 55%. More than half of unemployed youth have never worked, without experience you aren’t hired, without hiring you don’t gain experience. At the same time, the NEET rate has reached 43.2% (2024), with young women hit hardest.

In the Middle East and North Africa, youth unemployment was 28.0% in 2023, with women at 38.5% versus 25.7% for men. The NEET rate reaches 33.2%, the highest in the world, and for women it hits 46.3%. In countries such as Jordan, Tunisia, Iraq, Algeria, the numbers are explosive. Informal work dominates, young women participate minimally in the labor market, and education guarantees neither work nor a decent income.

In Latin America, the core problem isn’t only unemployment but informal work as “normality”: six in ten young people who work are informal, without contracts or social protection. In Brazil, informal work among youth aged 15–19 reaches 59%, falling to 40% (20–24) and 34% (25–29), showing that entry into the labor market begins in the shadows.

In the Philippines and Southeast Asia, the picture includes major skills mismatches, high NEET rates, and difficulty accessing work for those without university degrees. Even when overall unemployment is relatively low, youth unemployment remains high.

The common thread everywhere is one: young people are systematically excluded. Labor markets protect insiders and push youth into precarity, informal work, waiting, or migration.

A Glimmer on the Horizon

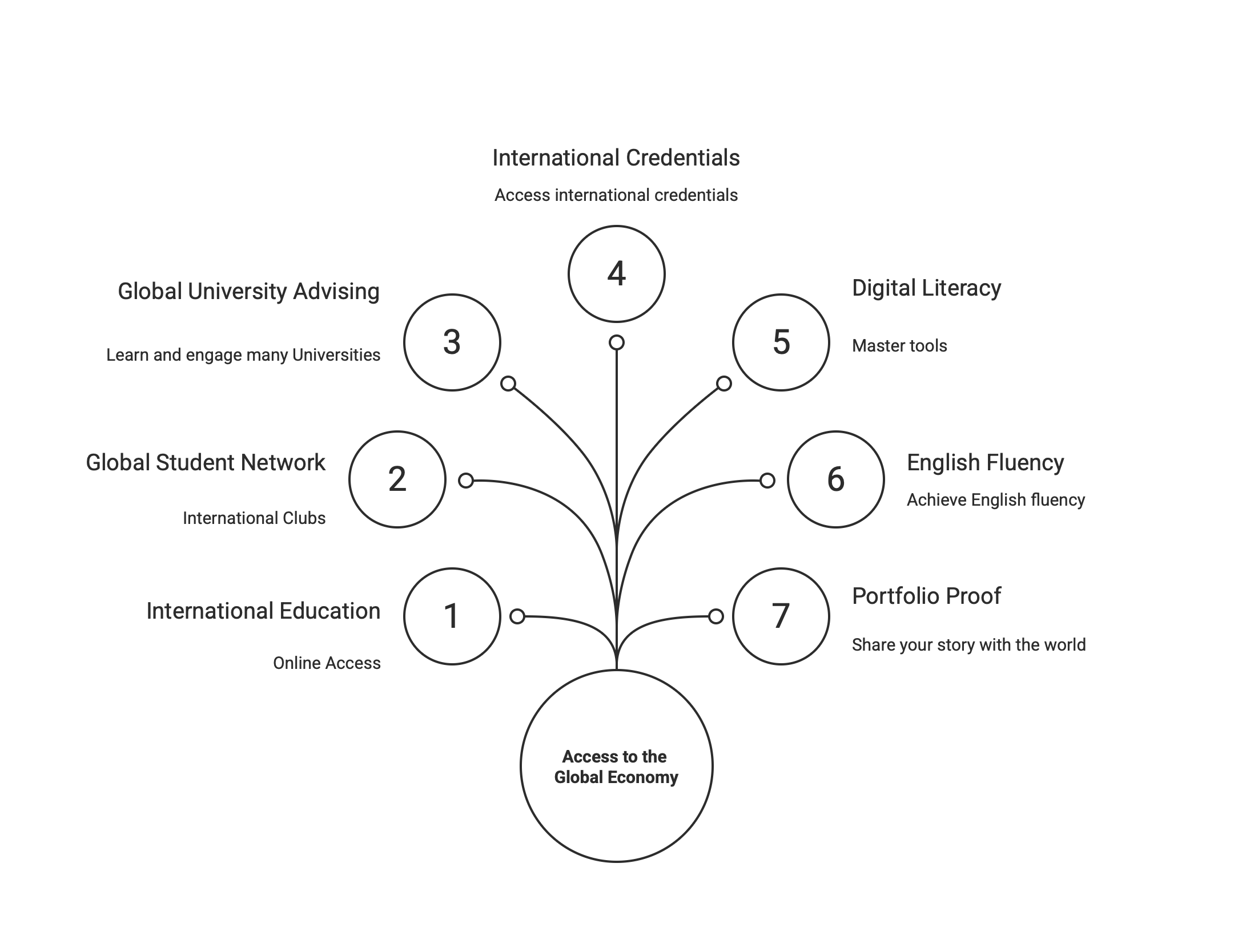

And yet, in this dark landscape, an escape route has already emerged, one that bypasses the gatekeepers: online education combined with remote work and global digital income.

The revolutionary element is that this shift begins before university, starting in middle school and high school. Platforms such as Khan Academy (180+ million registered users by 2025), Coursera (124 million learners), and edX (95 million) provide access to top-tier content, skills, and projects. Early access changes the trajectory: a 15-year-old can learn Python, data analysis, or digital marketing, build a portfolio, earn certificates, and enter the market with skills and proof of work, not with “zero experience.”

The model scales inside schools as well. Khan Academy, through partnerships with school districts, expanded from 40,000 students (2023–24) to 700,000 (2024–25), with a target of over 1 million (2025–26), offering dashboards, teacher training, personalized learning, and AI tutoring. Coursera integrates company micro-credentials (Google, IBM, etc.) into educational institutions, while some certificates also gain academic recognition through ECTS recommendations.

AI dramatically accelerates this transition: tutoring tools function like a personal teacher 24/7, offering something that used to be the privilege of those who could pay for private lessons.

International dual diploma programs, such as those offered through Hudson Global Scholars, enable students to earn an internationally recognized high school diploma alongside the Greek one without disconnecting from their school. Through online courses with certified U.S. teachers, access to AP courses, systematic English reinforcement, and participation in an international student community, students gain real experience of international classrooms, collaboration, and academic expectations, while fully retaining the option to sit for the Panhellenic exams, if they choose.

The outcome is twofold: on the one hand, the student builds strong academic foundations and 21st-century skills (communication, collaboration, digital competence, creative problem-solving) that prepare them to pursue admission and opportunities at universities worldwide; on the other, they gain meaningful access to the international market for study and work—and, by extension, to the global economy—through familiarity with international standards, work in cross-cultural teams, and the ability to participate in opportunities that are not geographically constrained.

The economic logic is clear: instead of years and tens of thousands spent on pathways that lead to temporary contracts and salaries of €900–1,400, young people can invest a few months and modest cost into in-demand skills, find remote work or freelance projects, and gradually build income, independence, and options.

According to the Coursera Learner Outcomes Report (2023), 91% of learners in developing economies reported career benefits from online education, while about 30% of unemployed learners found a job after completing courses. For entry-level Professional Certificates, about one in four found a new job. It’s not a cure-all—but it is a real pathway.

The remote economy and freelancing scale this possibility even further. Estimates point to roughly 1.57 billion people in the global freelance workforce in 2025 and a market exceeding $500 billion. Young people in Africa, Asia, and Latin America learn skills online and sell them globally via platforms, bypassing licenses, guilds, and local exclusion.

There are, of course, huge barriers: three billion people still lack internet access, many schools lack infrastructure, the pandemic excluded hundreds of millions of children from remote education. But the trend is clear: connectivity is rising, device costs are falling, networks are expanding. The question isn’t whether the transition will happen—it’s whether it will happen fast enough so an entire generation is not lost.

Marco, the aspiring taxi driver in Athens, ultimately left for Berlin. He drives for a ride-sharing app, earns three times as much, and saves for his own home. For parents and educators, his story is not just another example of “brain drain.” It is a reminder that if young people have to leave in order to breathe professionally, then we must give them a plan before they reach the airport. We must equip them early with languages, digital skills, international academic experience, confidence in working with people from other countries, and above all the ability to create value in markets that aren’t limited by borders. It isn’t enough to “get into a university.” They need to be able to compete in a world where opportunities, jobs, and projects are global, and often remote.

The crucial question for us isn’t whether Southern Europe’s model is viable. It is whether we can, through school and home, build more doors of access for our children to the global economy before “leaving” becomes the only option. That means seeking educational pathways that open international choices (not only local ones), investing in programs and experiences that offer internationally recognized credentials, and shifting the conversation from “what job will you find here” to “what problems can you solve anywhere.” Because if our societies keep preserving the present as it is, without upgrading the skills and opportunities of the next generation, then the cost won’t be theoretical: it will be the loss of our children—and with them, the loss of the future.

%402x.svg)

%401x.svg)