In 1945, with the world still reeling from the Second World War, American engineer and visionary Vannevar Bush delivered a report that would reshape how nations think about science, education, and innovation. Science, the Endless Frontier, written at the request of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, argued that the U.S. government had both a responsibility and a strategic imperative to invest in basic scientific research, develop talent, and establish public-private mechanisms to drive discovery in peacetime.

Bush’s vision was revolutionary: if the state could fund and coordinate large-scale innovation during war, why couldn’t it do the same in peace? He proposed a decentralized, university-led model of scientific research supported by the federal government. This model would feed the economy, improve public health, and secure national progress.

Bush laid out five enduring principles: sustained federal support for basic research; academic freedom centered in universities; a permanent civilian science agency (eventually realized as the National Science Foundation); intentional investment in scientific talent through fellowships and education; and strategic application of science to national needs like medicine, agriculture, and technology. These ideas defined the postwar American innovation model and were widely replicated globally.

Countries such as Germany, Japan, South Korea, and Finland adapted the Bush model to their unique contexts. Germany created the Fraunhofer Institutes, blending public research funding with private industry application, with a €3 billion annual budget today. Japan aligned its industrial policy through MITI, helping transform its economy into a technology and automotive powerhouse. South Korea focused on aggressive investment in education and R&D, spending nearly 5% of GDP on research and climbing into the top 10 of the Global Innovation Index. Finland, meanwhile, embedded equity, teacher autonomy, and strong public funding into its education system—resulting in both innovation and inclusion.

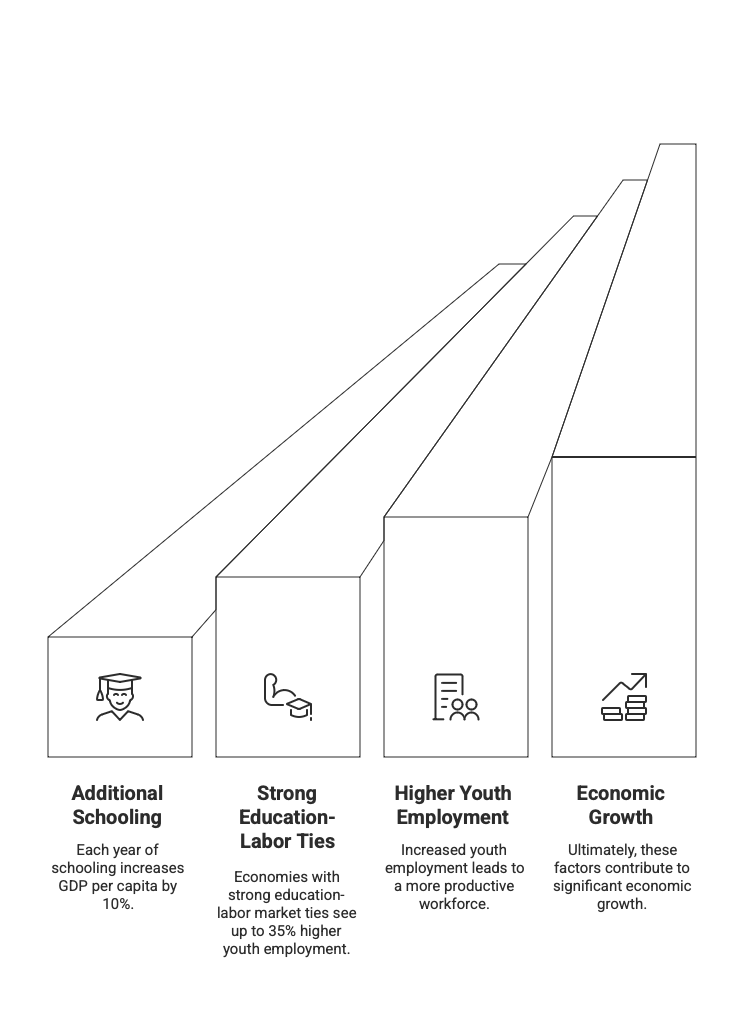

Across these models, one theme persists: public-private partnerships in science and education are central to economic growth. According to the World Bank, each additional year of schooling contributes to a 10% rise in GDP per capita over time. The OECD notes that economies with strong ties between education and labor markets see up to 35% higher youth employment. Moreover, nations that blend private innovation with public investment in education outperform in innovation outputs by over 40%.

The results of Bush’s framework were transformative. In the following decades, U.S. Federal investment in basic research—rooted in universities and sustained through institutions like the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health—unlocked breakthroughs from antibiotics and semiconductors to the internet and space exploration. By the 1960s, nearly 70% of all global Nobel Prizes in the sciences were awarded to American researchers, many of whom had benefited directly from the policies Bush championed.

The economic return was just as significant. Between 1950 and 2000, total factor productivity—the portion of economic growth not explained by capital or labor—accounted for over one-third of U.S. GDP expansion, with economists attributing much of that to innovation driven by publicly funded research. Each dollar invested by the U.S. government in basic scientific research has yielded an estimated return of $8.60 in GDP growth, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER, 2022). These investments created new industries—like biotech, computing, and aerospace—and gave rise to entire ecosystems of innovation, from Silicon Valley to Boston’s Kendall Square. The result has been higher GDP per capita, greater resilience, more substantial human capital, and more inclusive growth. In retrospect, Science, the Endless Frontier, demonstrated that innovation is not a byproduct of prosperity—it is its foundation.

A Shared Challenge in Different Forms

In Greece, students face one of Europe's most rigid academic pathways. Entry into public universities depends almost exclusively on performance in the national Panhellenic Exams. The high-stakes nature of this system pushes families to invest heavily in private cram schools with uncertain ROI results in most cases. According to the Hellenic Statistical Authority (2023), over 75% of Greek high school students attend such institutions. Yet this heavy dependence on shadow education exacerbates inequality and often narrows, rather than expands, academic flexibility.

To address this, the innovators of the private schools across Greece are now partnering with International accredited embed or online high school program providers to offer students dual diplomas—their Greek Apolytirio and an International High School Diploma. Between 2020 and 2024, enrollment in these programs grew by over 300%, with more than 1,200 students now participating across 25 campuses. These students gain access to broader university options, particularly in the U.S., the U.K., and the EU. They often secure scholarships at significantly higher rates than their peers who follow the Greek national path alone.

In Italy, students are placed into specialized academic tracks like the Liceo Classico or Liceo Scientifico by age 14, limiting cross-disciplinary learning and creating early specialization. Though Italy’s public universities are low-cost and relatively accessible, fewer than 18% of students study abroad, mainly due to language barriers and bureaucratic hurdles (Eurostat, 2023). In recent years, over 35 private international schools in Italy have launched dual diploma and online AP programs in collaboration with global providers. Students enrolled in these hybrid pathways show significantly improved language fluency, with over 60% reaching CEFR C1 proficiency, and double the university acceptance rates of students who stay within the national curriculum only.

Then there's South Korea, often praised for its rapid ascent as a tech-driven economy, underpinned by a disciplined and high-performing education system. But this success has come at a cost. The country has one of the world's most intensive shadow education cultures, with over 80% of high school students enrolled in private academies (hagwons) and families spending more than $20 billion annually on after-school lessons (Korean Statistical Information Service, 2022). Despite high PISA scores, students report among the lowest levels of well-being in the OECD. The pressure to perform in the Suneung (college entrance exam) drives inequality and burnout, prompting South Korea’s government to consider capping after-school hours and expanding public-private hybrid alternatives.

Across all three countries, a typical pattern emerges: centralized national systems and high-pressure entrance exams create excessive dependence on tutoring, limit innovation in learning, and constrain student agency. In contrast, the rise of international online programs and dual diploma systems provides a path toward more personalized, flexible, and globally connected education.

Students in these programs benefit from asynchronous learning, interdisciplinary electives, and direct mentorship from university students who become tangible role models to emulate their best practices for selecting the right university path for themselves. The structures of their national systems no longer exclusively define their destiny. Instead, they are linked to global higher education ecosystems, improving their academic mobility and competitiveness in international admissions and scholarships. Families in Greece and Italy report returns on investment of 3–5x in terms of financial aid packages, elite university placements, and language acquisition when students complete hybrid dual diploma tracks. Further, it informs parents about their options, truly augmenting their understanding about their university preparation and seeking options early on in their kids' high school years, saving them valuable resources and time. In South Korea, growing demand for online international options is beginning to reshape what success in secondary education looks like—moving from exam scores to long-term adaptability, creativity, and global readiness.

Vannevar Bush’s call to action in 1945 was a belief in the power of supported, decentralized, and talent-driven innovation. His five-pillar framework—fund research, empower universities, build infrastructure, invest in talent, and serve the public good—continues to influence how modern economies build progress.

Today, that same framework is taking root in secondary education. Around the world, collaborations fuel economic growth and open new doorways for young learners. In countries where national education systems remain rigid and shadow education fills systemic gaps, hybrid models offer something far more lasting: dignity, equity, and direction.

From Athens to Seoul to Florence, students discover that their futures don’t have to be confined by national tests or inherited systems. With the rise of borderless classrooms, the “endless frontier” Bush envisioned may begin much earlier, where the foundations of science, creativity, and global citizenship are laid not in research labs, but in high school living rooms connected by the internet.

%402x.svg)

%401x.svg)